Important: Disclaimer

This site is no longer active

Since August 2023 we have moved our content to a central Signpost Site

This is not the official site but a store of technical documents and ongoing work. Opinions expressed in posts are not representative of the views of NHS England and any content here should not be regarded as official output in any form. For more information about NHS England please visit our official website

Increasing understanding of coding activity associated with online consultations through OpenSAFELY (onboarding pilot project)

Date: September 2021 (Covering work from Jan-21 till Jun-21)

Last updated: 14th December 2021

Post author: Martina Fonseca - Senior Analyst, NHSX

Research team: NHSX Analytics Unit, NHSE/I Digital First Primary Care - in collaboration with OpenSAFELY

Git repository: opensafely/OS_OC_v001-research (to be made open)

note 1: this study and its outputs have been approved by NHSE/I as meeting the stated project purpose - including open release

note 2: as the open Safely framework is continually developing, some of the technical detail and issues discussed here may be out of date

note 3: the work carried out was a collaboration between NHSX AU, NHSE/I Digital First Primary Care and OpenSAFELY but the narrative in this piece is personal rather than organisational

OpenSAFELY

OpenSAFELY is a new secure analytics platform for electronic health records (EHR) in the NHS. The platform, developed by the Data Lab at the U. Oxford and partners at the start of the pandemic, uses a novel approach for enhanced security and timely data access that means there is no need to migrate outside of, or view at an individual record level, large volumes of disclosive pseudonymised patient data hosted in secure environments managed by the EHR software companies (e.g. TPP, EMIS); instead, it relies on trusted analysts to run arms-length computations and analysis on near real-time on records still held inside these secure environments.

Late last year, NHSX and the Analytics Unit were given the opportunity to become the first external collaborators to work on the OpenSAFELY platform. Our lead data scientist Jonny Pearson wrote about the journey and main learnings from this first collaboration.

Earlier in the year, we were given the opportunity to take part in the OpenSAFELY pilot for onboarding external approved users and researchers. To continue the shared learning while also supporting the wider digital transformation agenda that NHSX is leading, we made use of OpenSAFELY to better understand the implementation and utilisation of online consultations (OC) systems in primary care, in particular its coded activity in primary care records. This piece outlines some of the main learnings, takeaways and outputs from this pilot project.

Adoption of online consultation systems

NHSE/I, through its Digital First Primary Care (DFPC) programme, has been working on enabling the adoption and use of online consultation systems as a means to increase choice and flexibility for patients in accessing and receiving care and supporting practices to signpost and triage patients to the correct member of staff or service, prioritising care on need and optimising use of wider primary care roles.

An online consultation enables a patient to contact their GP, other health professional or GP practice staff over the internet, typically by using a smartphone, tablet or computer. It may, among other functionality and outcomes, also result in a written-form online consultation (See glossary for distinction).

The NHS Long Term plan (pre Covid) committed to every patient having the right to digital first primary care by 2023/24 with a commitment in the GP contract for 21/22 for all practices to offer online and video consultations. OC capability is believed to stand close to 95%.

An evaluation of the digital first approach in response to Covid-19 has been commissioned and is ongoing. Wider efforts on improving intelligence for operational, research and evaluation purposes are also underway.

OpenSAFELY was identified as a means of providing rapid and rich intelligence on the OC landscape, in particular during the pandemic. In this initial discovery piece, we looked at:

- understanding coding use and prevalence in primary care records by codes of interest, over time and in terms of national variation

- understanding broad demographics and past clinical history of those associated with online consultation-relevant codes

Piloting and using OpenSAFELY - the external collaborator view

One of the main strengths of OpenSAFELY is the richness of the documentation provided, covering both ‘Getting Started’ guides, ‘How To’ tutorials and extensive reference material.

The OpenSAFELY team also provides active and timely support via the GitHub Q&A forum and a dedicated researcher Slack channels.

The first step in this discovery piece was defining the set of primary care codes relevant to online consultation systems, to be queried. After initial desktop research and stakeholder input, the OpenCodelists builder was used to define an 18-item codelist. This tool can be used by anyone to create, curate and re-use codelists. While the codes chosen were not exhaustive or exclusive to online consultation systems, they were considered of most relevance to proxy its roll-out, ahead of moves for improved codes to be introduced and operationalised.

Made easier by the documentation as well as other existing study repositories available on the Github, open-source tools were used, including:

- Python: for defining the cohort and generating dummy data to test the code;

- Github: to host the full study repository, so that it can be accessed and run in the EHR secure environments servers when required, but also crucially for version-control and promotion of open, collaborative and transparent ways working;

- R: for data analysis and visualisation, though other tools including Stata or Python can also be used.

The dedicated jobs server was then used to request for the code to be run against the real data - always at arms-length within the server. All these request logs are shown transparently. The outputs of interest (trendlines, summary statistics, model outcomes) were then made available to the research team, after review for disclosure by an Accredited ONS Safe Researcher.

Tips

Some tips for analysts, from current experience:

- Define a fixed scope question and check feasibility based on available coding practices and literature;

- Understand limitations of coding to proxy patient profiles or service activity (see here for a main overview) and ensure the final outputs reflect those caveats in the narrative and technical appendices;

- Make full use of the rich documentation and Q&A forums;

- Look into other public OpenSAFELY repositories and publications to understand the art of the possible and how to implement these. Many of the approaches are easily transferable and adaptable!

- Though running code on dummy data can already help maximise chances that the code is fit for purpose when run on real data, breaking up the code, actions and jobs into smaller chunks and ensuring that the code produces informative logs and has fail-safes can really help when it comes to running and debugging code on the actual data, at ‘arms-length’.

- Generate summary outputs as editables - that is, SVG images, html tables - so that these can be re-designed outside of the server if need be.

Insights from the discovery piece

All the direct outputs can be found on Github and a more comprehensive report has also been shared with stakeholders. Some highlights are shown in the Appendix below.

Some insights include:

- More needs to be done to consolidate and harmonise coding practices for online consultations in primary care

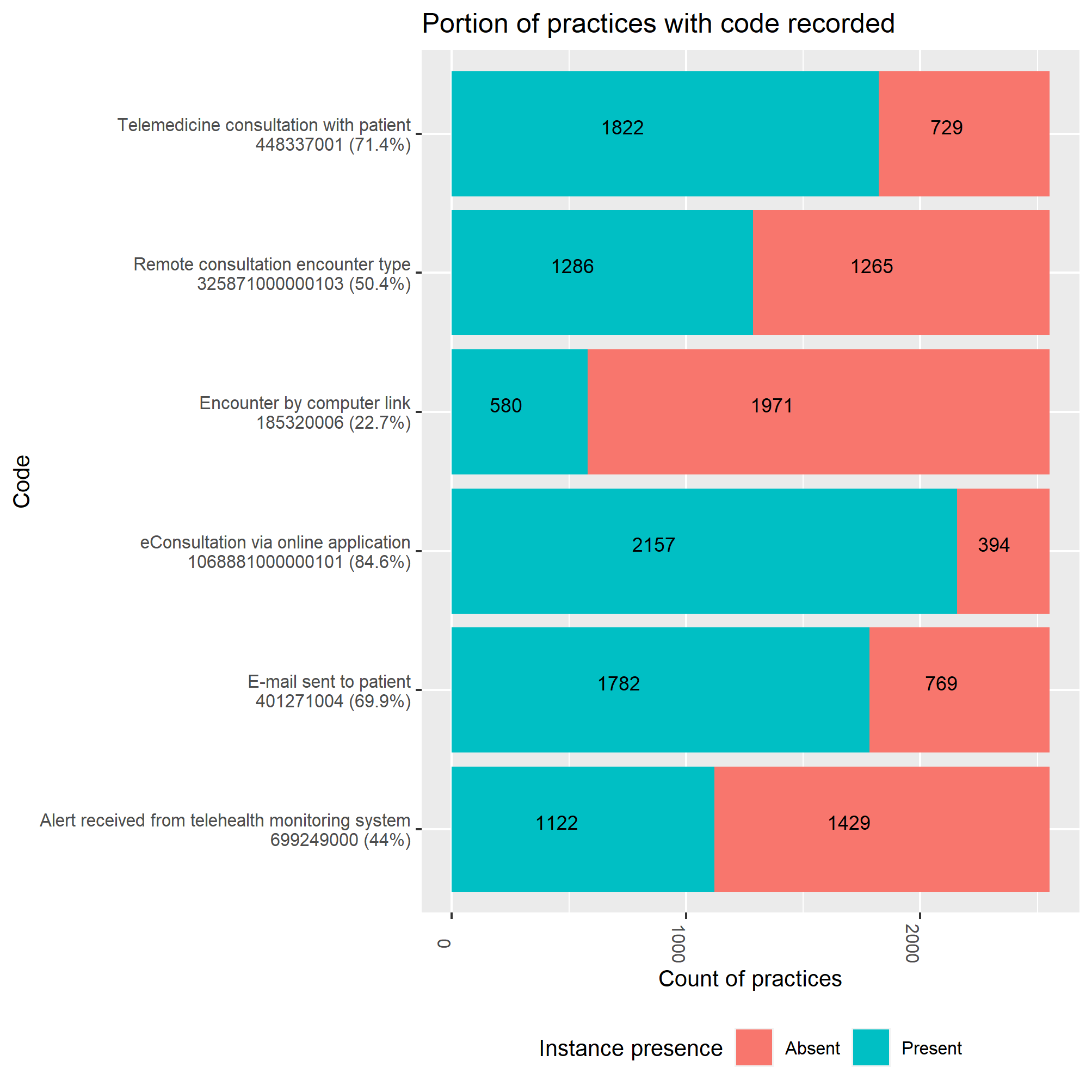

- Six of the eighteen codes defined were in active use in TPP practices. The ones used by more practices were, in order, eConsultation via online application, Telemedicine consultation with patient and E-mail sent to patient - in 70% or more of practices (Figure 1). EMIS practices also had registered activity for these codes, but their volumes were quite different, indicating likely differences in digital supplier systems, coding approaches or population served.

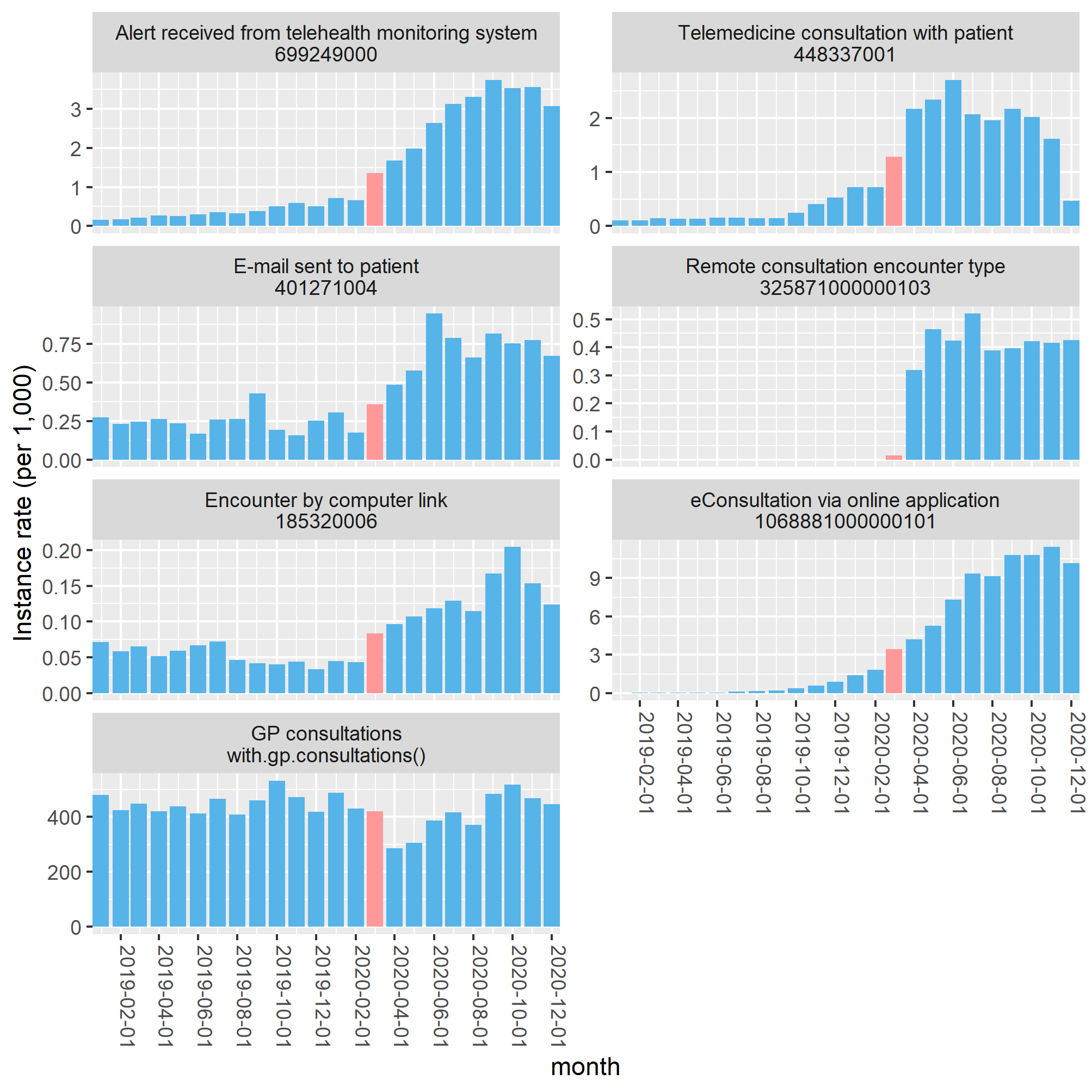

- As expected, contrary to overall GP consultations, which dwindled at the start of the pandemic, coding activity related to digital forms of interaction picked up rapidly from March 2020. In the second semester of 2020, over nine monthly eConsultation coding events per 1,000 registered population were registered, compared to less than one per 1,000 a year prior (Figure 2).

- When compared to the full practice population, or to those that had consulted their GP at all, the cohort of patients that had any recorded online consultation activity in 2019-2020 tended to (Table 1):

- Has a higher preponderance of female patients;

- Has a higher relative preponderance of those aged 18-40, followed by those aged 40-50 and 50-60;

- Skews more towards white patients;

- Skews more towards those least deprived

- We also found early indications that patients with online consultation coding activity (specifically ‘eConsultation’ as code) were more likely to have a clinical history of asthma, depression or heart conditions than other patients with any overall GP consultation activity in the same period of time - it is important to note though that the OC systems user profile may not be generalisable and may be very dependent on the practice-by-practice implementation model

Final thoughts

Insights from this discovery pilot study help build the picture around the implementation and use of online consultation systems and can support ongoing discussions on differential patterns of uptake as well as conversations with practices, OC system suppliers and EHR suppliers on ensuring consistent and widespread coding practices. Areas of interest for future exploration include:

- Development of coding activity metrics as proxies for wider coding quality and primary care activity (including sources of variation by organisation or patient sociodemographics);

- Facilitation of research and evaluation studies. For instance, for those with eConsultation events, how many need to re-consult within a month?

More than anything, this project was a great opportunity to collaborate and learn new stretching skills and techniques from DataLab and OpenSAFELY collaborative colleagues as well as subject knowledge from NHSE/I DFPC. It is also a great blueprint for the wider Data Strategy:

- OpenSAFELY is a powerful tool for researchers and analysts to generate insights from healthcare data, while ensuring appropriate data protection. This contributes to aspirations set out in Chapter 5 of the DHSC Data Strategy, on empowering researchers with the data they need to develop life-changing treatments, models of care and insights.

- Its use of open source tools, version control, web user interfaces and rich documentation is also in line with the desired direction of travel for ways of working in the NHS and for health and social care analysts across, namely with ambitions set out in Chapter 3 of the draft DHSC Data Strategy, on building analytical and data science capability, working transparently and in the open, encouraging sharing practices and collaborations with partners.

Glossary

-

Online consultation system: An online consultation system enables patients, carers, or practice staff on a patient’s behalf, to securely submit structured written information about symptoms, issues or concerns including administrative requests to their practice asynchronously online. There are various online consultation tools which offer different functionality to support practices with triage, navigation and providing care using the most appropriate consultation method based on patient needs and preferences (this includes face to face, telephone, video or online written consultations). Many tools provide additional functionality, such as the ability for patients to send photographs or for practices to proactively ask for information from patients (e.g. in relation to Long Term Condition reviews).

-

Written online consultation: A written online consultation is a two-way written exchange between a healthcare professional and a patient using an online medium (such as an online web platform or SMS). Such exchanges offer an alternative route of access for patients alongside telephone and face-to-face consultations.

Appendix - Highlight figures and graphs

Figure 1. Portion of practices with any recorded activity for online consultation relevant codes in general practice (January 2019 - December 2020). Codes with no activity at all omitted. Only for practices using the TPP supplier system

Figure 2. Monthly code instance rates per 1,000 registered population of SNOMED codes in TPP general practice (January 2019 - December 2020). March 2020 indicated in pink. Codes with no activity at all omitted. Only for practices using the TPP supplier system

Table 1. Characteristics of the studied cohort (TPP system), both overall and by a) patients with any form of GP consultation in 2019-2020; b) patients with any OC code instance in 2019-2020

| Group | Characteristic | Overall | Had any GP consultation | Had OC coding instance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Total | N = 20,651,036 | N = 17,166,765 | N = 1,087,919 |

| sex | Female | 10,260,731 (50%) | 9,172,833 (53%) | 661,235 (61%) |

| Male | 10,389,976 (50%) | 7,993,645 (47%) | 426,654 (39%) | |

| Other/Unknown | 329 (<0.1%) | 287 (<0.1%) | 30 (<0.1%) | |

| age [2] | - | 41 (22, 59) | 44 (24, 61) | 43 (27, 58) |

| Age group | (0,18] | 4,298,691 (21%) | 3,279,485 (19%) | 147,313 (14%) |

| (18,40] | 5,738,142 (28%) | 4,295,711 (25%) | 349,162 (32%) | |

| (40,50] | 2,842,130 (14%) | 2,353,934 (14%) | 176,261 (16%) | |

| (50,60] | 2,913,528 (14%) | 2,577,374 (15%) | 178,461 (17%) | |

| (60,70] | 2,269,212 (11%) | 2,137,624 (13%) | 124,470 (12%) | |

| (70,80] | 1,673,588 (8.2%) | 1,627,530 (9.6%) | 74,886 (6.9%) | |

| (80,Inf] | 746,742 (3.6%) | 729,284 (4.3%) | 30,036 (2.8%) | |

| Unknown | 169,003 | 165,823 | 7,330 | |

| ethnicity | Asian | 1,252,414 (6.1%) | 995,568 (5.8%) | 43,196 (4.0%) |

| Black | 412,399 (2.0%) | 318,858 (1.9%) | 14,157 (1.3%) | |

| Mixed | 249,470 (1.2%) | 189,299 (1.1%) | 10,708 (1.0%) | |

| Other | 6,026,577 (29%) | 4,775,182 (28%) | 289,469 (27%) | |

| White | 12,710,176 (62%) | 10,887,858 (63%) | 730,389 (67%) | |

| living alone | - | 5,783,003 (28%) | 4,733,553 (28%) | 316,542 (29%) |

| region | East | 4,823,404 (23%) | 4,014,256 (23%) | 200,338 (18%) |

| East Midlands | 3,618,902 (18%) | 3,036,933 (18%) | 160,425 (15%) | |

| London | 1,340,024 (6.5%) | 940,810 (5.5%) | 62,586 (5.8%) | |

| North East | 963,807 (4.7%) | 812,460 (4.7%) | 3,494 (0.3%) | |

| North West | 1,843,088 (8.9%) | 1,587,452 (9.2%) | 120,462 (11%) | |

| South East | 1,357,871 (6.6%) | 1,119,208 (6.5%) | 121,340 (11%) | |

| South West | 2,838,383 (14%) | 2,410,816 (14%) | 251,541 (23%) | |

| West Midlands | 861,670 (4.2%) | 699,715 (4.1%) | 21,112 (1.9%) | |

| Yorkshire & The Humber | 2,997,813 (15%) | 2,540,057 (15%) | 146,558 (13%) | |

| Unknown | 6,074 | 5,058 | 63 | |

| deprivation quintile | Q1 (most) | 4,157,772 (20%) | 3,376,403 (20%) | 167,889 (16%) |

| Q2 | 4,032,329 (20%) | 3,297,000 (20%) | 209,375 (20%) | |

| Q3 | 4,259,619 (21%) | 3,545,312 (21%) | 236,391 (22%) | |

| Q4 | 4,052,737 (20%) | 3,409,747 (20%) | 235,705 (22%) | |

| Q5 (least) | 3,796,821 (19%) | 3,238,612 (19%) | 219,527 (21%) | |

| Unknown | 351,758 | 299,691 | 19,032 | |

| rurality | Other | 328,860 (1.6%) | 281,603 (1.6%) | 18,154 (1.7%) |

| Rural | 4,113,110 (20%) | 3,578,049 (21%) | 216,578 (20%) | |

| Urban | 16,209,066 (78%) | 13,307,113 (78%) | 853,187 (78%) | |

| care home | Yes | 37,137 (0.2%) | 35,080 (0.2%) | 2,592 (0.2%) |

| Non | 20,613,899 (100%) | 17,131,685 (100%) | 1,085,327 (100%) |

Showing n (%) except for [2] which shows Median (IQR)