Important: Disclaimer

This site is no longer active

Since August 2023 we have moved our content to a central Signpost Site

This is not the official site but a store of technical documents and ongoing work. Opinions expressed in posts are not representative of the views of NHS England and any content here should not be regarded as official output in any form. For more information about NHS England please visit our official website

In this weeks digest we explore the software supply chain, single board computers and bloom filters.

In best practice, we look at software development and distribution as an encapsulation of processes, people, organisations and distributors. In technology of the week, we explore the intersection of software and hardware using single board computer (SBC). Finally, in algorithm of the week we cover the probabilistic data structure known as the bloom filter.

Best practice

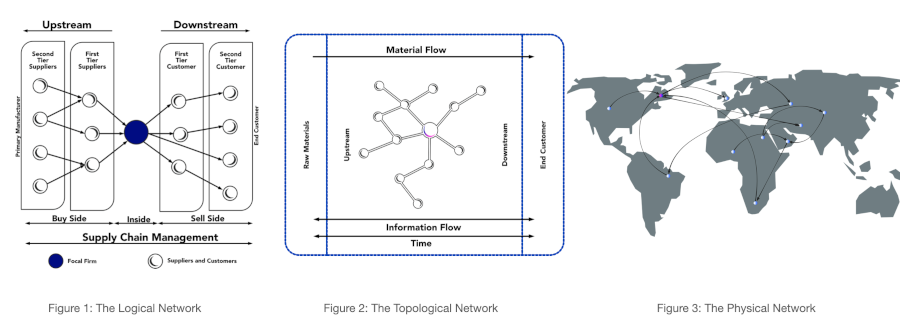

The software supply chain is not the digitisation of the physical supply chain. So what is the difference? Supply chain and logistics, as a discipline, has centuries of research devoted to the logic and optimisation of processes for life support systems, global commerce and war (life support systems to war…sigh). Supply chain and logistics and the associated domains of operations research and operations management, are literally battle tested. These interrelated fields focus on the optimisation of processes and services, the production and distribution of physical widgets in a timely manner and the movement of raw material through several value adding steps. The process is illustrated below:

More recently, discussions about the physical supply chain has incorporated the concerns that have arisen from digital commerce. The software supply chain is distinct and associated with software engineering and information security (cybersecurity). However, the software supply chain does share many analogues with the physical supply chain. The distribution of software extends to physical media and hardware devices and many physical supply chains are managed using digital tools and cyber-physical systems. Put it this way, if the software supply chain and physical supply chain had a Facebook profile their status would probably switch between “in a relationship” and “it’s complicated”.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) explain the software supply chain as the network of retailers, distributors and suppliers participating in the sale, delivery and production of hardware, software and managed services. There are threats associated with the software supply chain that exposes companies to: vulnerable packages; compromised pipeline tools; and compromised code integrity. These risks include but are not limited to:

- Code reuse

- Software Vulnerabilities

- Technical debt

- Typo squatting packages/domains

- Counterfeiting

- Outsourcing

- Malware

- Phishing

- Social engineering

- Malicious Code Injections

- Failure to patch

Supply chain threats are found at various stages of the software development life cycle. Due to the interconnected nature of software development and distribution, a compromised codebase can propagate through the network and have impacts far and wide. The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) published a white paper covering the threat landscape for supply chain attacks and provides a useful taxonomy for the software supply chain and supply chain threats.

The SLSA framework is a set of standards that can be adopted to improve the integrity of artefacts moving through the software supply chain. The framework specifies levels of assurance, in a common language, that describe the level of security hardening and steps taken to prevent unauthorised modification of software.

It is worth noting that not all developers agree with the view that they are suppliers in a software supply chain.

Technology of the week

![]()

![]() “S-B-C. What is it good for? Absolutely

“S-B-C. What is it good for? Absolutely nothing everything - say it again!” ![]() I love single board computers. I treat them like Pokemon, “Gotta catch ‘em all!” They offer the opportunity to write code that interfaces with sensors and other data gathering electronics.

I love single board computers. I treat them like Pokemon, “Gotta catch ‘em all!” They offer the opportunity to write code that interfaces with sensors and other data gathering electronics.

There is a classic grudge match, dare I say beef (Wagyu grade), that is never discussed in polite company. Hardware engineer vs software engineer. The two obviously need each other but I have heard many a hardware/electrical engineer exclaim “I’m not a software engineer” and many a software engineer say “That firmware was not written by a software engineer” (chat GPT and Copilot side-eye emoji here). Friendly jibes are thrown back and forth but is does seem that when software developers were asked “ Which tools do you need?” We answered with an emphatic “Yes!” We then received all the tooling, and more javascript frameworks than there are stars in the night sky. However, when hardware engineers were asked the same question, they replied with a definitive list:

- Assembly;

- verilog or VHDL;

- C/C++;

- RTOS;

- Unix;

- Spice; and a

- 555 timer

Seriously you need to see what some hardware hackers can do with a 555 timer there is even a yearly competition. A couple of really nice projects:

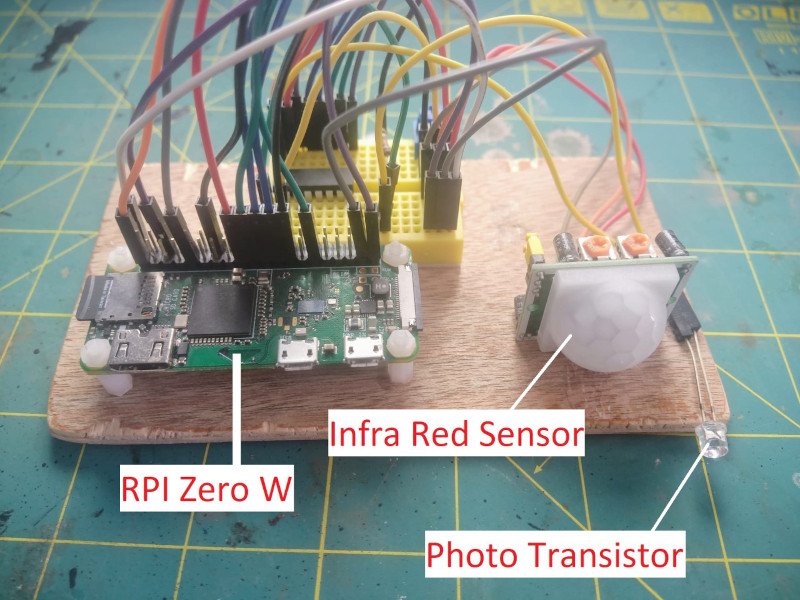

We also have some members of the team who dabble in the arcane art of hacking on hardware. Christopher Todd (Senior Digital Analyst) recently showcased a side-project using a PIR sensor, raspberry pi zero and some vnc magic to create a remote controlled lighting system. Below, Chris shares an overview of the project:

“The project uses sensors to measure movement and light levels in the room. When movement is detected and ambient light is below the threshold, the bulb is switched on for 10 minutes. The bulb remains on until no movement is detected for 10 consecutive minutes. Brightness is continuously adjusted based on the light measurements. At the centre of the project is a Raspberry Pi (RPI) Zero W. This is a smaller version of the mainline RPI models that sacrifices processing power in exchange for being smaller, cheaper and with lower power consumption.Movement is measured using an infra-red movement sensor, and light levels measured using a photo transistor. Both sensors are connected to the RPI via its General Purpose Input Output (GPIO) pins, and the outputs accessed within a Python script. The python code runs a loop that continuously polls the sensors and determines if any commands should be sent to the bulb. If a command needs to be sent, the smart bulb has a RESTful API endpoint. This allows it to be controlled by sending an API ‘PUT’ request in the standard format, using the Python requests’ package. An added benefit is the RPI’s low power consumption allowing the device can be left plugged into a mains socket to run continuously.”

The code for the project can be found on GitHub.

Algorithm of the week

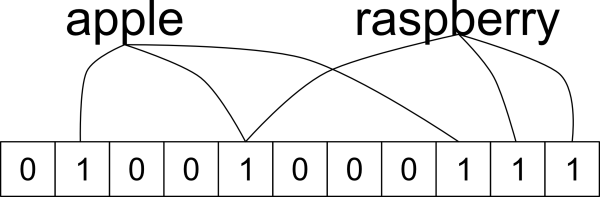

The Bloom filter is a simple but powerful data structure used to quickly identify whether an element \(s\) is a member of a set \(\mathcal{S}\). A bloom filter uses a \(n\) length bit array, where the bits \(b={\{0,1\}}^n\).

The filter requires \(k\) number of hash functions which will convert an entry \(s\in\mathcal{S}\) into the output that is between \(0\) and \(n-1\) i.e. selects for an entry in the bit array. The hash functions are \(\mathcal{H={\{\mathcal{h'}_{1},\dots,\mathcal{h'}_{k}\}}}\). For example, we use \(k=3\) meaning we have 3 hash functions:

\[\begin{align} h'_{1} = x \text{ }mod \text{ }n \\ h'_{2} = x^{3}-3 \text{ }mod \text{ }n \\ h'_{3} = x+2 \text{ }mod \text{ }n \\ \text{Where: }x=\text{the integer representation of } \mathcal{h}(s)\\ \mathcal{h}=\text{cryptographic hash function e.g. SHA256} \end{align}\]The cryptographic hash ensures we return the same unique value for \(\mathcal{h}(\mathcal{s})\). Cryptographic hash functions are deterministic and will return the same value should the same element \(s\) be hashed by the same function. This allows us to find entries that have already been seen before.

If we take the set:

\[\mathcal{S}={\{\text{apple, raspberry}\}}\]Each item in the set will be hashed three times and return a value within the \(1\times n\) dimension bit array thanks to trusty \(mod \text{ } n\). We can now insert a value of \(1\) for each hash function represented by \(k\) for each \(\mathcal{s}\in\mathcal{S}\):

There will be collisions and overlaps but the purpose of the bloom filter is to check the possibility of the entry and then retrieve. It is possible under this system to get a false positive but not a false negative. Calculating the probability of a false positive is beyond the scope of this post but is a step that can be explored.